Have you ever heard of Amelia Earhart (1897-1937)? According to history, this author & aviator wrote:

“You haven’t seen a tree until you’ve seen its shadow from the sky”

Sounds wise on the surface, but is it true? Without detracting from her many achievements, her own words imply she may never have “seen” a tree. Let’s review and maybe we can think of trees differently. Would you really like to see a tree and see it differently? Then I offer:

“You haven’t seen a tree until you’ve watched it grow”

Do not read further if learning about trees is of no interest. This is the most in-depth blog post I have ever added. There are several aspects offering insight about tree and redwood development ranging from seed germination to whether General Sherman Sequoiadendron is really two trunks instead of one. Actually, this entire page was inspired by Sherman’s bark, trunk (s) and shapes.

( Brief interjection: This page was inspired by General Sherman Sequoiadendron, and claims about it being one tree. Even DNA may not clarify whether Sherman is one bole. Trees can propagate extra boles in youth when low limbs “layer” into soil and in centuries enlarge and merge with same DNA. But differing DNA can prove that 2 different trunks merged. Also, Sherman has not been proved to be just one trunk – that’s an assumption and belief. More about this below)

I have been in planes before and seen shadows from the air but that didn’t allow me see trees much better. It was certainly a different way to view forests blanketing mountains. But honestly, if you stand over a seedling tree you’ve seen it’s shadow from the perspective of the sky. Continue reading below image:

The photo shows new seedlings with other plants near a coast redwood called Spartan. This is one step in our journey to genuinely seeing trees. There is plenty to learn and more than most of us can remember. Even seeds have requirements to grow and many are very different from each other. Some tree seeds (Sorbus) need to be below freezing for about 30 days. Others may need light. Others may need dark.

Coast redwood (Sequoia) seeds need time and vast numbers of them to survive in the wild. It takes about 1,000,000 seeds to equal a pound. Very few survive on their own and studies imply the seeds are more viable from older trees. A 20 yr. old redwood’s seeds are like 1% viable. Optimum viability is supposed to be from redwoods 250 years and older but even those reach no more than 5% germination. Fungi, falling debris and changes in moisture hinder many. In light of this, that’s why the seedlings above caught my attention. I rarely see coast redwoods germinated from seed.

For the more part, tree seeds have no choice. Redwoods do not “prefer” certain places like humans do. If tree seeds land in the right conditions they are virtually powerless to resist. Whether they survive is a different matter. But if a birch seed lands in a moist gutter of old leaves it will germinate and grow for a while. I’ve seen Japanese maples growing in gutters too, and not looking to the mountains of Japan for their needs. Trees can germinate high in other trees and also inside homes. They do not choose, but react and obey certain conditions.

I have worked professionally with tree care and planting for over 40 years with 10 more years caring, pruning and observing as a youth. 50 years isn’t much but it was enough where it may be safe to say I’ve “seen a tree”. 5 years of golf course work offered some extra insight. I used to prune trees at several country clubs. Dozens of species, watching them change weekly and yearly. All grew at different rates, varying with conditions. Different size trees drooped branches more or less than one another by summer letting me know how much to remove in following winters for each size and species. Giant sequoia in soggy ground would turn red in winter and grow miserably, warning not to repeat the mistake of the person who planted it. Western redcedar in the same soggy soil rebounded more vigorously in spring showing it’s tolerance. All that took time to watch, recognize, remember and “see”. That understanding never came from 10,000 feet.

Even the inside of a trees provide insight. For who-knows-how-many-years, gardeners and professionals used tree wound paint to coat pruning cuts and “wounds”. Decade after decade they damaged trunks and wood not realizing what was true. Part of the problem was not getting close enough for a good look. Forget 10,000 feet – even two feet away was insufficient. At one point in time people noticed more rapid closure of cuts after sealer was applied and assumed it was the right thing. They had no idea they were damaging the tree and wood. Continue reading below image:

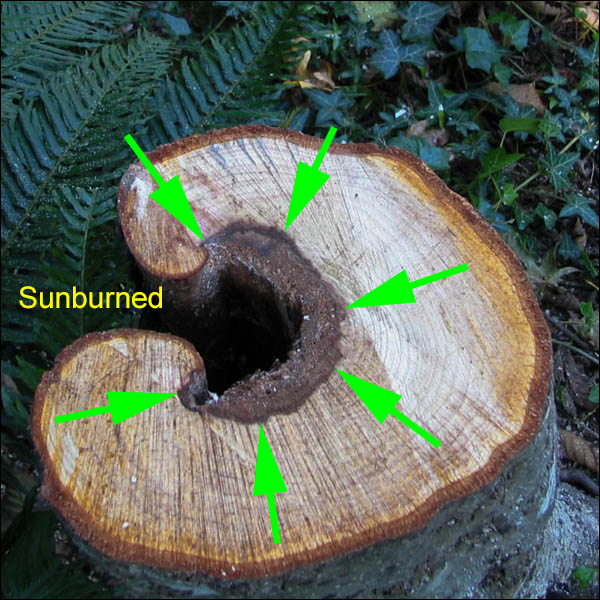

Trees, including redwoods, can naturally compartmentalize decay from good wood. The photo above is not a pruning cut but shows how trunks compartmentalize. The arrows point to a darker zone of defense produced by the tree after sunburn damage killed cambium and started decay. With smaller pruning cuts, trunks will naturally set up the same kind of defense and if the wound can dry on the outside (cut side) it’s better. But sealers trap moisture and aid decay, interfering with the tree’s own inherent ability. Notice how the tree’s darkest barrier is in close to the wood unlike sealers that were applied toward the exterior.

Similarly the chunk of wood below shows where a giant coast redwood compartmentalized decay from the rest of the wood. Continue reading below image:

That was a huge chunk that fell from El Viejo del Norte. About 500 lbs. among many tons of fallen debris. The dark brown left is a large mass of “canopy soil”. The green arrows mark where El Viejo compartmentalized decay (darker brown interior), hidden for centuries until it fell. The red arrows mark the edge of reddish orange heartwood adjacent to the lighter sapwood. The same thing shown in the previous sunburned trunk is happening in this giant coast redwood.

(Interjection – That’s what’s destined to fall on the new metal boardwalk. Wonder if the rubes thought-that-one-through for future costs !!)

So after decades of well-meaning but ignorant cut painting, researchers and others began dissecting trunks and learning from the insides. If storms dropped trees that were previously cared for by “tree surgeons”, those casualties had value for study. Plus thousands of trees were planted and wounded on 4 sides to apply sealer. One wound left untreated, then 3 different sealers for the 3 remaining wounds of every trunk. Then years passed, to cut and study more of these plots. The final conclusion was don’t seal. It’s better to let the wound close slower, dry out and allow the trunk set up it’s own internal barrier.

One weakness that occurs in nature are “V” shape unions. Other “U” shaped unions are stronger but nature doesn’t care. That’s why urban tree can’t follow a “hands-off” natural approach that a small handful of arborists commit to. If nature breaks it merely recycles and replenishes. Around landscapes and gardens people prefer the most years they can get from a tree. In nature, we don’t see what nature took care of, but we only see what remains.

The trunk below split at a “V” shaped union. Had the broken stem been removed at planting time when it was merely 2 inch diameter this would not have happened. I always prune-out this type of weakness when planting and even select trees without this form if available.

There’s a lesson here related to coast redwoods too. This is how many goosepens began and were formed. Those small caves on the sides of trunks. Many began small like this form. Then the trunks grew to 8 ft. or 15 ft. diameter and one trunk peeled away during a storm. The exposed wood dried, ready for fire to burn, and decay to rot. Over many years the cavity expanded size to become the small caves we call goosepens. Continue reading below image:

Here’s a coast redwood trunk below. The same basic thing happened. There used to be another trunk many years ago, then it split away. Sometimes the fallen trunk remains but usually the fallen part seems to be absent having vanished as centuries of decaying pass by.

If you read this far, and if I expressed myself clearly, what I expressed near the beginning should be evident at least partially. For trees to be seen it requires time and watching them grow, fall and die.

May as well go one step farther !

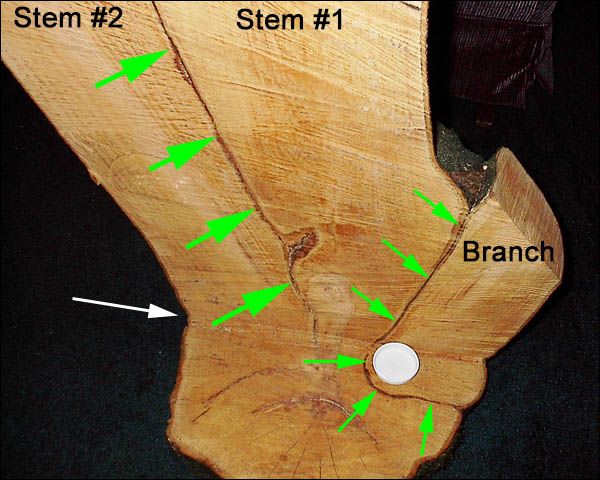

When stems or trunks emerge and rise with a “V” shape union between them, weakness is often the result. It hinders the production of wood between, and the opposing bark surfaces move inward with growth and just touch. It’s not a bond or union, and can get weaker each year as the trunks get heavier. I will illustrate with this trunk section taken from a flowering plum tree. Continue reading below image:

Let’s decipher the photo. Two cuts were made to expose the interior. One cut downward and one crosscut sideways. The two cuts meet at a crease marked by the white arrow. A lens cap sits flat on a part where a branch became included. There were at least two trunks stems and one branch. Lack of pruning resulted in weak “V” unions, trapping included bark. The green arrows mark the included bark. It’s very tightly pressed, but not actually attached, and very weak. Tree’s like this can easily tear apart from wind or water and snow weight.

Other trees do the same thing, including coast redwoods. It also happened to General Sherman Giant Sequoia. Amateurs and rangers likely would never notice, but the signs are evident. Yes … General Sherman is not a single stem tree, which means it’s not the largest single stem tree in the world. Now, I’m stating this as what I believe from experience rather than ascertained fact.

Someone replying on Facebook said I can’t prove this. Likewise, they can’t really prove it’s a single trunk! It’s well-known to researchers and arborists that coast redwoods and even Sequoiadendron have grown adjacent to each other swelling into what looks like a single column or headed that way. It’s a fact that has been ascertained.

Without cutting open a living giant and without testing, one can only guess whether a trunk is from one single bole or from two boles. But if a trunk holds indicative signs, that’s more convincing than nothing to go on.

Continue reading below image:

General Sherman appears to be a double trunk (“fused”) Sierra redwood known as Sequoidendron giganteum. Determining included bark and twin stem origin isn’t tricky, but there’s more than one thing to look for. Some trees of single stem origin can also have small amounts of included bark. But when one side of what looks like a main trunk has a linear indent or inclusion that’s an obvious clue. A second clue is when that linear indent reaches up 1/2 or 2/3 of the trunk’s height. When the same evidence is on both opposite sides for considerable distance it’s likely the mass is two very old double trunks expanded into each other hiding included bark. But it rarely hides everything just as the plum trunk above retains a very slight indent a few inches to the right of the lens cap. The trunk flare (footprint) or ground level buttress shape of twin trunk form can also be an extra feature since it tends to have cleavage.

Best I can tell from standing and photos, some largest Sequoiadendron are not actual single trunk formation, and near a dead-heat with coast redwoods for largest single trees. The two species are so close that an average visitor wouldn’t be able to realize which is really the biggest.

This is the same way we learned Howland Hill Giant (HHG) is a twin stem redwood. It can appear like a round bole seeming singular, showing that doubles don’t have to be elliptical. In fact, sometimes there are triples or quadruples like the 2nd tallest redwood in the world. I remember taking the expert measurer Chris Atkins (read THE WILD TREES) to the HHG. He walked around to a certain viewing angle and barely a minute later confirmed HHG must be formed from 2 trunks. As interjected top of this page about Sherman, a DNA test would be handicapped if an extra merged bole were from layering or a root sprout centuries ago. Hopefully finding observable signs and evidence of shapes are practically more telling.

(2022 update – Over 10 years after seeing the Del Norte Titan in the Grove of Titans, I just learned that it’s a double stem. April 28, 2022, I wandered through a patch of head-high ferns around a big depression in the earth where I’d never stood before. This gave a clear view. It was possible to see remnants of the old individual trunk shapes. In another 500 years that could swell with more growth and vanish)

Shadows and curvature remaining from twin trunks becomes easier to see in certain lighting conditions. It’s something 99,000 out of a 100,000 people may not look for.

Good cross lighting helps, like how photographers place lights at 45 degrees to get portrait and Rembrandt lighting. Lighting that doesn’t show this kind of detail is like Nat Geo’s December 2012 giant sequoia photo where snow and overcast reflect fill-light from every direction erasing shadows.

Adding a human example, look at the man to the right being cross-lit with a studio light. In plain daylight his muscles would never appear that defined. The cross lighting also defines his facial features. This is the opposite effect of “fill light” which can “smooth” skin almost better than makeup.

Back in the years when I worked at golf courses, we would start work in the dark around 3 am to prepare for tournaments. Then we would park the Cushman carts and mowers on the opposite side of the greens. The headlights shining directly across the greens would show shapes and defects that were virtually impossible to see in daylight hours. We did that to place pins in legit but brutally tough positions. Light can be relied upon in the same way to accentuate the shapes and detail of redwood trunks.

The image below is about the best example I have on hand to convey how I think Gen. Sherman became what it is after about 2000 years. The photo shows 3 redwood trunk that are probably 500 years old. The round shape of each one is going away as inner surfaces facing each other flatten and squeeze together. In about a few hundred more years, it may seem like just one trunk, but vertical lines should still be somewhat evident for 100 feet or more. After 1000 years, the lines may disappear completely or leave traces.

Continue reading following image:

A good number of you probably know of the corkscrew tree in Prairie Creek park, shown below. Some people say things like this are a mystery. But everything in the coast redwood forest has a cause. And the corkscrew redwood provides enough clues and facts to explain how it developed this form. Continue reading below image:

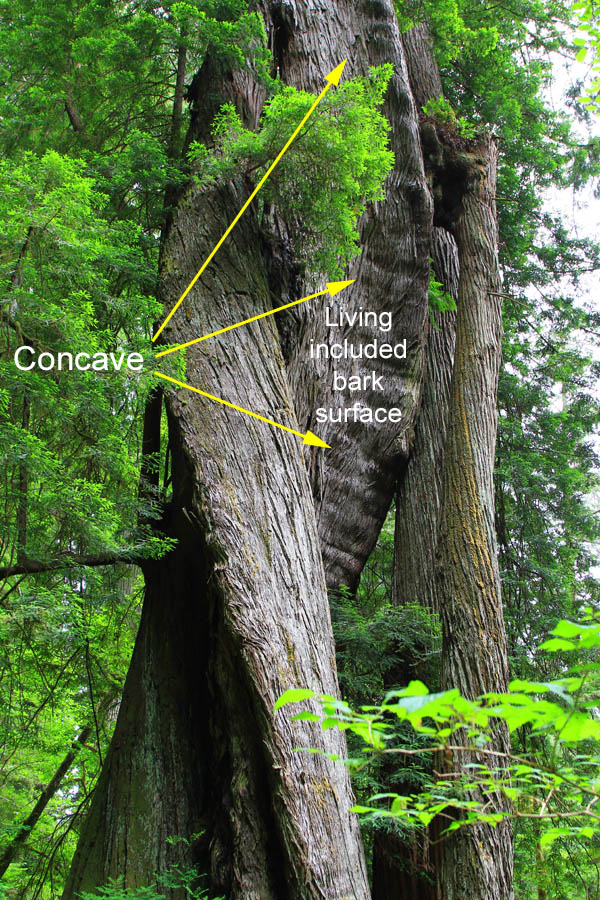

First, that redwood has a lot of exposed concave bark surface. Most coast redwoods have exposed convex bark surface. Second, the concave bark is alive. This tells me that the bark used to be included bark, wedged between it’s trunk and a large dead trunk that since then, decayed and vanished over several centuries. Why did I say a dead trunk? Because the included bark is large, alive and substantially formed – emphasis on alive.

The trunk below shows a medium size stem removed from next to a larger stem of the same tree, where the smaller stem interfered overhead with roof, other trees, etc.. But look at the included bark. The bark trapped between is dead, even crumbling near the edge. The growth of cambium and tree tissue can exert up to 170 lbs. per sq. in. pressure. The expansion of both stems over time with that much pressure eliminates life and growth for the included bark, tightly sealing it within. Also notice the slight concave curvature; minimal, but present. Continue reading below image:

Because both stems were solid and living, there was nowhere for cambium and bark to expandbetween. This is why the living bark of corkscrew redwood is evidence of a dead trunk in it’s midst. Dead decayed wood is often spongy.

Because decayed wood can be soft and spongy, it means it has “give” and will yield to the pressure of 170 lbs. per sq. in. and trunk growth. It still offers enough resistance to mold and shape another trunk’s growth, but enough give to keep the bark from perishing. Here’s one more example below showing convex included bark where a tree’s branch expansion met it’s own stem expansion. I removed the limb to allow more tissue growth for the future. Continue reading below image:

These characteristics and tendencies of trees indicate part of the history behind corkscrew tree and part of it’s shape. But there are several ways trees can be shaped and formed in unusual ways. It can be caused by man, the trees, environment, or the tree itself after something within or environment changes it.

Take bonsai for example. Men and women wrap copper wire around the branches and trunks and bend both to a new desired shape. After a couple years, the new wood formed in the new shape like a cast. In nature, snow pushes small trees into a lean, causing curvature as the new growth emerges straight upward again from that point. Trees can also curve on their own. The branch below basically grew this way. There was a type of internal cause, but it was not manipulated. This is flowering cherry. Continue reading below image:

So the corkscrew redwood did not grow or twist on it’s own like the new wood growth in that sample. If corkscrew redwood’s full bark exterior were normally rounded, I would entertain a different avenue of reason, but not with the concave included bark on it’s trunks. The shape of the corkscrew tree trunks is weaker and more flimsy than a full cylinder like other redwoods have. So the twist probably helped allow the change. But what caused it?

Wind has enough force to bend or even break stems. But the only other thing in the redwood forest with enough size and force to bend large stems are other falling or flailing trunks. The tree below is what led to putting all the pieces of the puzzle together. Continue reading below image:

The fallen trunk did not twist this standing twin stem tree on the right, but it’s perfectly aligned for illustration. The 2nd fallen piece on the right is a chunk that broke off the fallen trunk in the upper corner. But this reminded me of several similar examples I’ve seen hidden in the forest, which I hadn’t yet related to the corkscrew redwood’s shape. Apart from strong wind, falling trunk wood is the only force I’m aware of in the redwoods that can reconfigure the shape of other large redwoods.

This is what I believe happened to the corkscrew redwood. I can’t necessarily prove it, but it looks like that redwood has already proved it. Certain trunks probably decayed and vanished around it in the past few hundred years. But it kept all it’s shapes, bark and evidence to this day. And all of it means something.

As Jurassic as the redwood forest seems, there is very little mystery. And that doesn’t detract in the least. Understanding and recognizing changes in the redwood forest, for me, excels any mystery factor. That’s why I don’t buy into this phrase:

“And into the forest I go, to lose my mind and find my soul” (John Muir)

I prefer the head start of exploring the forest with both mind and soul. Much more can be recognized and realized going into the forest with both.

Recent Comments